By Rabbi Corinne Copnick

As we approach Rosh HaShana 5779, endeavoring to wipe our slates clean before the mandated behavioral change deadline, Yom Kippur, I find myself turning to the first pages of the Torah, Bere’shit, the beginning, the creation of the world we know.

In Bere’shit, the first chapter of the Torah, creation seems so awesomely simple, so beautiful. An all-powerful, omnipotent, omniscient, Divine force, whom we Jews call Adonai or HaShem, simply “speaks” our world into being from the vast nothingness of the tohu va bohu, the watery void. In a timeframe of only six “days”(on the seventh day, God sees that the creation is good – tov—and thus rests), the first thing God does is to create light, separating it from darkness, so that Day and Night became new concepts. Then God separates the waters so that we have both dry land (“Earth”) and “Sky.” The next step is to create vegetation on the earth, seed-bearing plants and fruit-bearing trees. And then comes the creation of the sun and moon, which brings set times of light and darkness (as well as years) into what is to become our world.

“God made the two great lights, the greater light to dominate the day, and the lesser light to dominate the night and the stars” (Genesis 1:16).[1]

Told biblically in prose, this cosmic story of the world’s creation is echoed so movingly in poetry in Psalm 136.

Who made the heavens with wisdom

His steadfast love is eternal;

Who spread the earth over the water,

His steadfast love is eternal;

Who made the great lights,

His steadfast love is eternal;

The sun to dominate the day,

His steadfast love is eternal;

The moon and the stars to dominate the night,

His steadfast love is eternal.” [2]

Now this beautiful world needs living creatures, so fish (even including great sea monsters) are brought forth to swim in the waters and birds to fly in the sky. Next come all kinds of animals ranging from creeping things to wild beasts to roam in the land — and finally Man. Adam, made in God’s image.

“And God created man in His image, in the image of God He created him; male and female He created them.”(Genesis 1:26).

Modern science has supplemented the Torah in showing that we all descend from one progenitor – all living creatures start from the same basic cell. But what about Eve, the first woman? Was she really created at the same time as Adam, as Chapter 1 tells us, or, in Chapter 2’s differing account, was she made instead from Adam’s rib, which would make her the world’s first clone? Some biblical scholars think that the two accounts were written by different authors in different time periods and pieced together by skillful editors. Others believe that both accounts are true and simply augment one another, the first concentrating on the cosmos and the second on humanity. I prefer to think that man and woman were created equal from the get-go. In any case, whether we choose Chapter 1 or Chapter 2 as our preferred account (or a combo of both), once males and females were created, the divine goal of populating the world proceeded. [3]

There is also the question of how long a period a day actually was before the set times were created. So, if we consider the biblical account as occurring in indeterminate stages of time (rather than 24-hour days), it actually coincides with the much later developed scientific time frame of our world’s evolution. While our modern society craves scientific proof for something so mystical, so infinite, so powerful as creation itself, surely that process goes beyond being “proven” to the satisfaction of our limited human intellects. Certainly, our earthly mathematicians know that numbers are infinite; why not the limitless energy of the Divine? What we call God. To wax kabbalistic, underneath every letter of the Hebrew Torah is a number. Ironically, we speak in numbers.

Like the once ubiquitous slates in the schoolroom, our ideas about creation have moved light years from from the world we earthlings know into infinite territories. We no longer think about earth as unique among the planets and stars, although it is unique to us. We explore the concept of many universes. We search for other planets where life may be possible. Surely, as humans, we are not alone in a universe so large our human minds strain to encompass it.

Traveling to the moon has already been accomplished. Now we talk about terraforming Mars so that human beings can live there, and already, as I write this D’var Torah, we are sending a probe to the Sun to better understand its energy. Unlike the mythical Icarus, who flew so dangerously close to the sun that his wings melted, today’s astro-scientists are unafraid, even as they speculate about multiple universes. For civilians, space tourism is becoming a possibility, provided they have the large pockets to afford it. For those who dare, will space settling become a reality? I am awed by what might be.

Awe, of course, is not a monopoly of religion nor of creative artists. Scientists experience awe too, as “a motivation to push them further,” explains Sara Gottlieb (working with Dacher Keltner and Tania Lombrozo) in a recent interview with Rabbi Geoffrey A. Mitelman on the website “Sinai and Synapses”:

Awe is traditionally seen as our reaction to things that cannot be reduced or explained…

[T]he process of accommodation, in which we adjust our beliefs in light of surprising new information, is felt just as often by scientists as by people who experience awe in other situations. [4]

Of course. Scientists are human beings with wide-ranging human reactions. It is religion’s job to interpret. In the awe-inspiring Torah account of creation, according to Richard Elliott Friedman, “the divine bond with Israel is ultimately tied to the divine relationship with all of humankind.”[5]. On a more mundane, current earthly level, we have do more than worry about over-population and feeding the planet in an era of climate change, we have to do, we have to work to make things better, all the while we continue to strive for an elusive peace between nations. I believe that, with God’s help and our own efforts, we will make progress, although it may take at least a couple of generations or more to see the results.

[1] Stein, David E. (ed.). JPS Hebrew-English Tanakh: The Traditional Hebrew Text and the New JPS Translation, 2nd ed., (Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 1999), 1-3.

[2] Psalm 136. Quoted in Gunther Plaut, Ed. “Essays,”The Torah: A Modern Commentary, 2100.

[3] “The Torah begins with two pictures of the creation. The first (Gen1:1 – 2:3) is a universal conception. The second (2:4-25) is more down-to earth. The first has a cosmic feeling about it. Few other passages in the Hebrew Bible generate this feeling. The concern of the Hebrew Bible generally is history, not the cosmos, but Genesis I is an exception. There is a power about this portrait of a transcendent God constructing the skies and earth in an ordered seven-day series. In it, the stages of the fashioning of the heavenly bodies above are mixed with the fashioning of the land and seas below.”– Richard Elliott Friedman, Commentary on the Torah: With a New English Translation and the Hebrew Text. (New York: HarperOne, 2001) 5.

[4] Sara Gottlieb (working with Dacher Keltner and Tania Lombrozo) and Rabbi Geoffrey A. Mitelman, Interview. “Awe As A Scientific Emotion,” www.sinaiandsynapses.org.

[5] Friedman, Commentary on the Torah.

©️Corinne Copnick, Los Angeles, 2018. All rights reserved.

By Rabbi Corinne Copnick

It’s a truism that just about everything is cyclical; eventually it all comes back into fashion, or history, or politics, or interest in who created the cosmos and what is there. Revival, recycling, regeneration: it’s a law of living. So I am not at all surprised at the new societal passion — in the midst of abundant visual imagery that has overwhelmed entertainment, merchandising, and education — for audio learning and entertainment, for audio books. Now once again, there is a thirst for hearing, for listening. Once again, individual imagination can exercise itself to see what isn’t there. Audio allows its audience to focus on the presentation to a greater extent, I believe, than when everything right in front of our eyes on a television or computer screen.

Television came to Canada (where I was born and lived most of my life) later than it did in the U.S. Up until then radio had been king, with the Canadian Broadcasting Company (CBC) the only national radio (with lots of local affiliates) heard across Canada. Everyone everywhere in Canada listened to the well-articulated, well-researched national news. In fact, the reliability of the C.B.C. was a source of national pride, a Canadian icon like the Mounties or the national railroad that connected the Western reaches of Canada with the Eastern ones. From sea to shining sea.

If you were to take a trip across Canada in the still golden radio years, every house that could would be tuned into the CBC. In the days before television and later the Internet, it was a national connector. When, as a teenage actress, I performed in CBC International’s “School Broadcasts,” I was thrilled that the scripted words I was enacting (very slowly for comprehension by an overseas audience just learning English) were heard by people so far away. For example, in a “Western” sequence, I might be stretching out the emotional content and enunciation of the words “No-o-o, d’o-o-o-n’t SH-O-O-O-T!!!”

Most people don’t know that, in my salad days, I was a professional radio actress on many CBC dramas. I actually began my radio career at the age of ten on “Calling All Children,” produced weekly on CFCF, a local Montreal station, by the Montreal Children’s Theatre (directed by Dorothy Davis and Violet Walters with an all-kid cast). I got my first professional role on the Lambert Cough Syrup Hour (CKVL, pre-union, it paid $5 for a 15-minute show), and by the time I was 12, I was auditioning – and getting cast in multiple roles – on the CBC (I was one of the first actors (#67) to sign up for ACTRA, our first professional actor’s association in Canada – and once we had a “union,” we got paid a magnificent $18 for a 15-minute radio broadcast, with an hour and 15 minutes rehearsal). Five days a week x $18 was good pay ($90) then for only one 15-minute radio serial when a man (not a woman) who was not an actor might be bringing home $25 for a week’s labor. Half-hour and hour shows (which we usually did on the weekends) were, of course, much better compensated. That’s how I got through university

Children’s Theatre (directed by Dorothy Davis and Violet Walters with an all-kid cast). I got my first professional role on the Lambert Cough Syrup Hour (CKVL, pre-union, it paid $5 for a 15-minute show), and by the time I was 12, I was auditioning – and getting cast in multiple roles – on the CBC (I was one of the first actors (#67) to sign up for ACTRA, our first professional actor’s association in Canada – and once we had a “union,” we got paid a magnificent $18 for a 15-minute radio broadcast, with an hour and 15 minutes rehearsal). Five days a week x $18 was good pay ($90) then for only one 15-minute radio serial when a man (not a woman) who was not an actor might be bringing home $25 for a week’s labor. Half-hour and hour shows (which we usually did on the weekends) were, of course, much better compensated. That’s how I got through university

The radio scripts were all accompanied by an organist live in the studio. Buddy Payne (who kindly played liturgical music at my wedding) led us musically from scene to scene, fading in the music for narrations and fading it out during the subsequent scene, or providing dramatic highlights to the script. For special radio productions – like “CBC Wednesday Night,” a much-listened to weekly show that produced quality scripts (more often from Toronto than Montreal) – a full, live orchestra accompanied the actors in the studio. What a great time we actors had with the fun-loving musicians in the CBC lounge we shared before the show!

But my radio and theatrical (I was active in local theatre too) career came to an end as, to our joyful surprise, my husband and I produced identical twins to augment the two young kids under five years old we already had. Wow, four kids under five! Acting had to take a back seat. Completely immersed in a joyful motherhood, I “retired” from show biz at 28 — for the first time. Radio would soon give way to television anyway, almost fading into the history books as visual entertainment and learning took over. Who knew that one day, so many years, and so many wide-ranging experiences later, I would become a rabbi, and that theatre experience is very useful in preparing and giving sermons?

In 5778, I wrote a D’var Torah for each weekly parsha and published them all on my website (www.rabbicorinne.com), where they can be individually accessed under the heading “D’var Torah”. You’ll find it on the home page’s sidebar.

Enter the Podcast.

In 5779, I plan to record these Torah commentaries as podcasts for, as they used to say in old-time radio, “your listening pleasure.” It was bound to happen. It’s cyclical, right? And people like to feel connected. So much of life in Los Angeles and other large cities is spent feeling isolated, non-productive, wasteful of time – on highways and congested streets. You can’t look at a screen and drive. The folly of text messaging has taught us that. So listening to something worthwhile, something ofyour choice, perhaps educational, or funny, or just plain entertaining reduces the tension of “getting there.” It can also be a motivational experience.

Listening provides a space for thinking new thoughts.

As the Torah – originally taught orally and only written down much later — instructs us, “Shema!” Listen. Listen and do good things.

©️Corinne Copnick, Los Angeles, 2018. All rights reserved.

Sitting in the Garden of the Finzi-Continis:

Time to Wake Up

By Rabbi Corinne Copnick

For the last twenty years, the members of my family and I – originally from the cooler climes of Canada – have been fortunate to be living in California, a landscape of uncommon beauty. Our garden is blessed with oranges, lemons, other delicious fruits, and the healthy vegetables we grow. Even grapes (rather small ones). Roses and other aromatic flowers bloom around us. We are shaded by tall trees and enjoy a solar-heated swimming pool. Just the other day, we drove my grand-daughter to the University of California at Santa Barbara, a stunning college complex overlooking a sandy beach. The campus is such a popular choice this year that a diversity of very bright students are inhabiting its residences three, rather than two, to a room. (In all fairness, I must mention here that my grandson is now in his second year at the highly-rated University of British Columbia, also a campus of great beauty.)

Yet increasingly, in the midst of all this natural and academic well-being, I am beginning to feel as if I am sitting in “the garden of the Finzi-Continis.” As those who are old enough to recall, this excellent movie, produced in the 1970s and based on a book of the same name, depicted the gracious life of a leading, wealthy Jewish family in Mussolini’s Italy in the 1930s. The refined family members are concerned with beautiful things, with their accomplished circle of artistic friends, with gentlemanly sports activities like tennis, and with a warm and welcoming hospitality that keeps the sinister political activity growing all around them at arm’s length. Until it encroaches on their own lives, ultimately destroying them.

Now it is 2018. And this is real life, not a film. What happened in the 1930s and 40s is, of course, history. Yet as a Jew and a Rabbi, I am shocked by the anti-Semitic “dog whistles” multiplying once again in the public sphere. In the U.S.A., welcoming land of liberty? How can I dismiss anti-Semitic sentiments when they come directly from the lips of a totalitarian Russian leader given free reign to express them on national American television. On CNN, for example, where I heard with my own ears Vladmir Putin insinuating that the Jews, not the Russians, were responsible for manipulating the U.S. elections. “Blame the Jews,” he said. “Maybe they were Jews with Russian citizenship.” The dual implication is that Jews in Russia cannot really be citizens, and, furthermore, that Israel is behind it all.

Putin’s despicable comments were REAL news. WHAT HE SAID WAS A LIE, BUT IT WAS REAL THAT PUTIN SAID IT. And, yes, Putin has been asserting this canard for some time.

For those of us who have witnessed malevolent times, our collective memory springs into action. Certainly, various Jewish groups in the U.S. have already protested. They have “compared Vladimir Putin’s comments about the 2016 election to anti-Jewish myths that helped inspire the Holocaust, “ wrote Avi Selk in the Washington Post (March 11. 2018).

Unfortunately, Israel (read Jews as subtext or vice versa) has been the recipient of anti-Semitic attacks from both the political far-right and the political far-left. The infamous linguist, Noam Chomsky, an internationally-known far-leftist – and for years a virulent antagonist of Israel years — has recently contributed to the mix by maligning Israeli lobbying in the 2016 election.

On both television, and in a Gatestone Institute column, lawyer Alan Dershowitz angrily referred to Chomsky’s downplaying Russia’s interference in the American elections, while, at the same time, Chomsky asserted that “the Israeli government’s influence operations are far more powerful [than Russia’s].”

The danger inherent in intentionally targeted words like Putin’s or Chomsky’s is that, as our Jewish history all too well testifies, they can and do incite evil actions. “Good” people — that is, those with ostensibly good intentions — usually don’t anticipate the malevolent actions that may result from those words. By the time, the “good” people wake up, it is often too late. The evil actions may have have progressed beyond what those with good intentions could have imagined, even in their wildest nightmares.

Even as I write this, even as I realize that there are gradations of good and evil, and that sometimes they intertwine, I continue to believe with all my heart that eventually good overcomes evil. The question is when. As humans, unfortunately, we have to adjust our time frame. The overcoming of evil actions takes time, sometimes generations Sometimes there is denial. It takes time for an entire population to sufficiently understand, that no matter how you sugarcoat it with lies, what is evil is not good.

©️Corinne Copnick, Los Angeles, 2018. All rights reserved.

By Rabbi Corinne Copnick

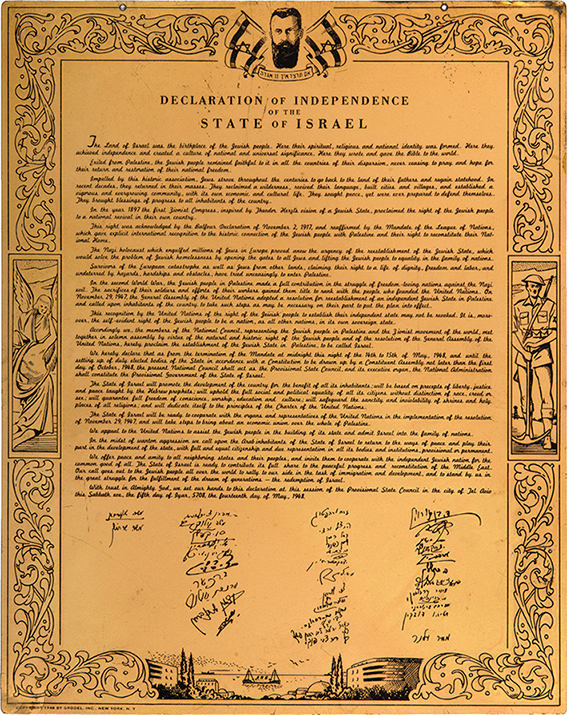

Image credit: https://www.kedem-auctions.com/content/copper-plaque-israeli-declaration-independence-new-york-1948-english

One of the good things about growing older is that you remember many historical events because they were personally lived. In 1948, I was 12 years old. I remember as if it were yesterday the excitement of my family and neighbors as we crowded around the radio, straining to hear the words of the courageous Declaration broadcast direct from the spiritual homeland that had only been a dream sustained by the dedication of those who had believed in it through the centuries. Israel was once again a national homeland for the Jewish people.

In the aftermath of the controversial Nation State Bill so recently passed by the Israeli Knesset, we would do well to remember the inspiring words of the Declaration of Independence proclaimed by the brand new State of Israel on May 14th (the fifth day of Iyar, 5708), 1948. These very words, inscribed on a brass plate along with the courageous signatures of people now well known in Israeli history, were given to my father in thanks for his help — among many other Canadian and American ex-soldiers who had helped Holocaust survivors make the difficult journey to the Promised Land — in establishing the State of Israel. This plaque has had a favored place on the wall of every home I have ever lived in since 1948.

Despite the assertion in the 1948 Independence proclamation that, as a national homeland for the Jewish people, Israel would be a welcoming place for everyone, history has recorded that the surrounding Arab countries (with their own catastrophic narrative) sent their armies – five armies — against Israel the very day after Independence was proclaimed. The brand-new Israel was able to hold its ground because it had no other choice. Despite countless negotiations and almost continuous hostilities, a lasting peace, 70 years later, has not yet been found.

Here is the excerpt from the 1948 Israeli Declaration of Independence that remains etched, not only on the brass plaque, but in my memory:

“The State of Israel, will promote the development of the country for the benefit of all its inhabitants; will be based on precepts of liberty, justice, and peace taught by the Hebrew prophets; will uphold the full social and political equality of all its citizens, without distinction of race, creed, or sex; will guarantee full freedom of conscience, worship, education, and culture; will safeguard the sanctity and inviolability of shrines and holy places of all religions; and will dedicate itself to the principles of the Charter of the United Nations…..

“In the midst of wanton aggression, we call upon the Arab inhabitants of the State of Israel, to return to the ways of peace and play their part in the development of the state, with full and equal citizenship, and due representation in all its bodies and institutions provisional or permanent.

“We offer peace and amity to all neighboring states and their peoples, and invite them to cooperate with the independent Jewish nation for the common good of all. The State of Israel is ready to contribute its full share to the peaceful progress and reconstitution of the Middle East. Our call goes out to the Jewish people all over the world to rally to our side in the task of immigration and development, and to stand by us in the great struggle for the fulfillment of the dream of generations – the redemption of Israel.”

Would that it were so. Amen.

By Rabbi Corinne Copnick

On my very first trip to Israel, almost four decades ago in 1979, I toured Israel flanked by the silver crosses of two Roman Catholic nuns.

“If you ever tell anyone you toured Israel with two R.C. nuns, no one will believe it,” laughed Sister Mary Lou, one of the grey-haired nuns. Later I would simply call her Mary Lou, and her companion, Mary Grey. They had just been decorated with huge silver crosses at an audience with the Pope in Rome. It was a reward for years of service and achievement, as was this trip to the Holy Land.

And so, in the summer of 1979, I walked between their two crosses in safety anywhere in Israel. Anywhere in the Old City. And to East Jerusalem at night. In 1979, it was already imprudent for foreign women to walk alone in Arab neighborhoods.

Actually, we had been thrown together, Sister Mary Lou, Sister Mary Grey, and I because terrorist attacks in 1979 were already plentiful. It was a time of bombs in market places and garbage cans. The tension was such that most tours were canceled that June. And so El Al Airlines (on which our motley group was traveling) organized a special tour for those passengers who wanted one. We were strangers, staying at different hotels, but united by the common purpose of wanting to see Israel from a religious and historical point of view. Each day a bus would pick up all the tour participants from the various hotels at which they were registered.

The only tour members staying at my hotel, the Moriah, were the two elderly nuns. Sister Mary Lou was plump and cheerful, her round, happy face creased from time to time with worry about her heart condition. The trip demanded a lot of exertion. Sister Mary Grey, tall and lanky, austere in appearance, and, at first, rather severe in manner, suggested we three have dinner together the first night. Rather glumly, I complied. Touring with two nuns didn’t fit my initial idea of fun in Israel.

The first evening was somewhat stiff as slowly we got to know each other a little. They were nuns from the Sacred Heart. This, I learned, was the crème de la crème of orders. (Through the two Sisters, I was soon able to meet a whole fraternity of Sisters from different countries.) And through the two Marys, I was able to see Israel with different eyes as well as my own. I was to learn how important this land was to them as well, to see through their eyes the places that mattered to them as Christians. And in turn, they would learn the places that were significant to me as a Jew and be enriched with widened perception as well.

That first night, however, we were just getting acquainted. Neither wore headdresses or habits. Later I was surprised to find they put curlers in their hair at night. Just like other people. I was not yet a rabbi; nor did I have any thought yet, nor would I for many years, that I wanted to be one.

Fast forward to two weeks later: Like happy schoolgirls, Mary Lou and Mary Grey spread out their “loot” for me to ooh and aah over on the twin beds of their hotel room. They may have looked like sorority friends chuckling over purchases in a college dorm, but I already knew that they were brilliant Ph.D nuns simply thrilled beyond belief on their last night in Israel. In the morning, they would return to their convents in New Orleans and Texas. In the meantime, they had bought out Israel. Candlesticks, menorahs, chalices, crucifixes, and linens cascaded all over the beds onto the floor of the hotel room, obscuring the carpet. They had bought presents for every bishop, priest, nun, and relative (an embroidered blouse for a young niece) they could remember.

“We’ll never be able to come back,” Mary Lou whispered, clutching her heart. “This is the trip of our lifetime.”

Mary Lou had gripped her bosom in horror earlier in the trip. We almost had to carry her out of Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial in Jerusalem. “We didn’t know, Corinne. We didn’t know,” she sobbed to me. I held her against me gently. “I’m sure you didn’t know, Mary Lou,” I answered softly, reassuringly.

They were wonderful nuns, splendid people. Side-by-sided with their two silver crosses, I attended the Bar Mitzvah of a thirteen-year-old tour member. His parents extended an invitation to the whole touring bus – now cohesive and groupy. Total inclusion. We sang the service happily together and sampled the Kiddush with gusto.

When I got home, I bought a six-pointed Star of David studded with little diamonds. I have worn it on a delicate chain around my neck ever since. It would be ten years before I would be able to visit Israel again.

©️Corinne Copnick, Los Angeles, 2018. Excerpted from my much longer article entitled “A Star is Born…” and published in The B’nai Brith Covenant, Toronto, Ontario, 1989.