By Rabbi Corinne Copnick

Over the past view months, Zoom online programming has been my window to the outside world. As it has with many of you, this new technology has made the viewpoints of my colleagues and friends available to me in these difficult pandemic times. I have learned so much from the thinking process and knowledge of others and offered my own as well. It has enabled me to see friendly faces I know, as well as those new to me, in mosaic tiles. And on Zoom, we can actually “see” one another, full face, for a while. We don’t need masks when we’re on the screen.

As a senior citizen in my eighties, I have the good fortune to live with two of my grown children and now a grandchild home from college as well. I do not have to watch television or have a Sabbath dinner alone. We have a beautiful garden in which to relax and have family meals outside. However, as a diabetic for the last 25 years, I do have a compromised immune system. So I have listened faithfully to the advice of our California government and our dedicated health experts and remained indoors since the beginning of March. It’s going on five months now. Apart from a daily walk around the block or so, and one quick visit to the beach on a day that it was “open,” I have not been “outside” since the “stay safe at home” instruction was issued.

At first I watched a lot of television, especially the daily comments of New York governor Andrew Cuomo, whose service to our nation has been invaluable. As a family, we caught up on recent TV series with “binge-watching.” We cooked and baked a lot. Courtesy of the Los Angeles library, I have read some thirty or so books online. Good books. I visited my doctor for an online appointment.

Perhaps most important, I have included in my daily schedule attending at least one Zoom lecture or teaching on a particular topic every single day. When it became too overwhelming—and tiring as well, because learning on Zoom requires a constant, single-focus attention, I restricted my Zoom screen time to one lecture a day. Gradually, I developed the confidence to successfully host and teach ten of my own sessions for my Beit Kulam adult education classes.

And I am proud to have mastered, at least to some small extent, and an online class helped, a new technology that can be a very “cold” medium for teaching—unless you learn how to make it “warm.” Recorded lectures tend to be on the cold side, and I have found that it’s best to have shorter bursts of “teaching,” with a lot of discussion, or guided discussion, in between.

Also, I find it takes away from concentration on what the main speaker is saying to have written material, or even visual material, on the screen while the speaker is talking. Better, in my experience, to use it, as an aid to discussion, before or after the topic at hand. At the moment, I’m not an enthusiast of the breakaway groups feature; so far, I have found this “small group” discussion experience rather limited in the time allowed. Still much to be learned about using it, so this reaction may change.

When I virtually presented my new book, “A Rabbi at Sea” in New York for the Jewish Book Council network, I saw how meticulous preparation and engagement could make a large scale event very successful. Where there’s a will—and a need that could otherwise be overwhelming—there’s a way!

* * * *

In the meantime, I have made myself available to my Beit Kulam members, should they have the need to talk about personal issues, on Friday mornings, and on Friday afternoons I virtually teach a private Torah class to my own daughter (I have four of them) and her non-Jewish partner in Vancouver. It has proved to be both a beautiful and calming experience before greeting Shabbat. Their “homework” is to read various commentaries about each week’s parsha before we read it aloud together. This past week we gave the gift of increasing strength to one another by reciting the traditional “Hazak, hazak, v’nitkazek” as the Book of Numbers ended and began Deuteronomy, the last book in the Torah, which largely summarizes what has happened in the previous four books.

So, for some people, the new technologies drive them nuts. For me, it has been a wonderful way to preserve my sanity amidst the labyrinth of dark and conflicting news broadcasts that now permeate our wonderful world. For me, the new technologies, bringing with them exposure to many points of views, are a saving grace. Can I help it if I’m naturally hopeful and optimistic?

I remember the devastating polio epidemic of my youth that so badly affected my mother’s cousin, Libbele, that she was paralyzed from the waist down for the rest of her life, confined to a wheelchair. But she had an indomitable spirit. She mastered many crafts, through which she made a small living, and her loving relatives made sure she was well supported, emotionally and financially, throughout her life.

Like the many other pandemics that permeate our world history (one of the four disasters that the Jewish holiday, Tisha B’Av, memorializes is the plague that killed 24,000 students of Rabbi Akivah), polio was eventually overcome (even though late age, second stage polio has unexpectedly entered our world) when Dr. Salk developed a vaccine. As I write this, our scientists around the world are working furiously to find the right vaccine to overcome Covid-19. With God’s help, they will. As Dr. Salk is famously quoted, “Hope lies in dreams, in imagination and in the courage of those who dare to make dreams into reality (www.salk.edu).”

By Rabbi Corinne Copnick

It was joyful, fantastic, overwhelming, and reinforced my belief that the catastrophic disaster called Covid-19 will eventually lead to world-shaping innovations that will improve our present society’s quality of life immeasurably. Call it a justification anew of that old adage: “Necessity is the Mother of Invention.” Call it the manifestation of a new, “woke” generation taking charge, sometimes overcharge. Call it a combination of education, science, ethics, the arts, and government—and a new regard for authentic historical experience of the past century and earlier (and the expertise of an older generation to which I belong that remembers it accurately because we’ve lived through it and its after-effects)—all working hand-in-hand to make life for human beings globally the best it can be in this new decade, the 2020s. Call it people have amazing inner resources when they are put to the test.

What great event stimulated my current overflow of optimism? It was the three-day conference of The Jewish Book Council (JBC), based in New York, but open to participants from all over the US and even beyond this year. Pre-Covid 19, for years this conference has been held in-person, providing an opportunity for writers accepted as touring writers of the JBC “network,” which, along with its many acclaimed authors, consists of member Jewish organizations from all over the country. It’s an exceptional opportunity not only to promote their new books, to present them in carefully-timed “pitches” and gain bookings before new audiences, but also to meet and greet, and feel that they are part of a literary whole that gives them new energy and inspiration to keep on writing.

Writing can be a very lonely business. So opportunities for writers to get together, especially in this year of Covid-19, where authors have been limited in large measure to telephone and computer screens, have loomed larger than ever. That is why the JBC in its wisdom, but taking on a huge task, decided to hold the conference virtually this year. Not only would the various member sessions be held virtually, but its writers also would present virtually. The outpouring of people who wanted to be included was phenomenal.

Making the virtual conference successful required meticulous and lengthy preparation, both for the technical aspects of such a large enterprise, for the member organizations, and for the writers. As a JBC network touring author, I had the benefit of Council staff working with me on two occasions to refine my presentation to the best it could be within the two minute requirement.

Why two minutes? Because over three days, eight groups of approximately 25 authors, each with substantial resumes and literary accomplishments, presented virtually to a member audience, also virtual, of a few hundred people taking notes. That’s a lot of authors to remember, even with a presenting cap of 2 minutes each (with a ding when your two minutes is up, just like the Academy Awards). For this reason, the JBC also put out a its own virtual (Pdf) book containing the details of each Council touring author’s offering and bio. In order to book an author for an event, the member organizations have to contact the Jewish Book Council.

We authors also were treated to a detailed technical rehearsal involving sound, lighting, when to keep our own video cameras and sound system on and off, an orderly procedure for each presentation, and so on. The technical people and administration throughout were not only supportive but very kind to people of different ages who had varied levels of experience with Zoom techniques. Everyone concerned put in their best effort. That’s why the conference—whose administration only a few months earlier could have conveniently canceled the event, was so successful that it is considering the possibility of going global next year. Wow!

And I think every single one of us who participated in making the conference successful, both for the organization and personally, feels very, very proud. Who’s going to let a virus, one that will probably be around for a long time, get us down? Of course, “broadcasting” from my own dining room table, with the technical assistance of my daughter, I didn’t have to wear a mask. But you can bet your bottom dollar I do and will wear one whenever it’s essential for me to leave the house (where I have mainly been sitting right beside my similarly housebound computer since the beginning of March). I want to be in good health to participate in next year’s conference.

Thank you once again to those who made it possible for me, mainly Miri, Suzanne, Naomi, and Jake—the personnel with whom I interacted, as well as all the writers who were in my presenting “cohort.”

Now we need some virtual bookings.

By Rabbi Corinne Copnick

Even though Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall didn’t star in a movie about Tangier (who has not seen their fictional romance in Casablanca unfold on a cinema screen?), this busy port-city in Northwestern Morocco has a history to rival Casablanca. Its location at the western entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar – right where the Mediterranean Sea meets the Atlantic Ocean — has given Tangier a trade advantage over the years to the extent that in 1928 it was deemed an international city. Its history as an important port goes back to the time of the Phoenicians in the 10th century B.C.E. History, history, history!

And even though Tangier today is a lively, modern city with attractive landscaping, affluent neighborhoods, and important projects, my daughter and I wanted to visit the old Medina with its colorful mélange of shops and signs. Although it was, in part, once a thriving Jewish neighborhood in Tangier, none of the shops retained names that were likely to be Jewish anymore.

Unlike other cities in Morocco, Tangier never had a mellah (a walled and gated area where Jews were required to live, ostensibly for their own protection) similar to the European ghettos. Nevertheless, the Jewish inhabitants of Morocco understood that they were living in an Arab, mainly Islamic neighborhood, and that certain restrictions applied to non-Islamic residents who lived in Arab lands, including Morocco. Although Jews and Christians were both respected as “People of the Book,” they understood that they were considered inferior to Muslims and expected to defer to them in many ways. In addition, they had to pay a special tax for the privilege of living in Morocco. Basically, they were second-class citizens referred to as dhimmis.

Most of the time, the different religious groups understood their place in Moroccan society and got along very well, but, regrettably, over the centuries (the 8th century and again in the 15th century in the city of Fez, in particular), some large massacres of Jews took place. Centuries later, during the World War II Nazi regime in Germany and the pro-Nazi, Vichy government in France (Morocco , remember, was a French protectorate), many civil restrictions on Jews were put into place –despite the best efforts of the Moroccan King to prevent them.

When World War II ended in 1945, and after its own War of Independence, the State of Israel became a reality in 1948, Moroccan Jews found themselves targeted by a forceful Arab push for them to leave Morocco. Those who had the means immigrated to countries like Canada, France, and South America. At the same time, there was a strong biblical pull for the larger number of Moroccan Jews who for centuries had dreamed of making Aliyah (the ascent of return) to their spiritual home, Israel. And so the mid-20th century exodus to Israel began. In 2019, an estimated one million Jews of at least partial Moroccan ancestry are Israeli citizens – who still have tender feelings for Morocco.

©Corinne Copnick, Los Angeles, 2019. All rights reserved.

By Rabbi Corinne Copnick

Just as my daughter and I had visited the lovingly restored, small synagogue in Casablanca, it was important to us to visit the old synagogue in Tangier, located by winding our way through the maze of alleys adjacent to the Bazaar (the shouk or marketplace). By pre-arrangement, our guide pressed a buzzer, and a custodian opened the gate.

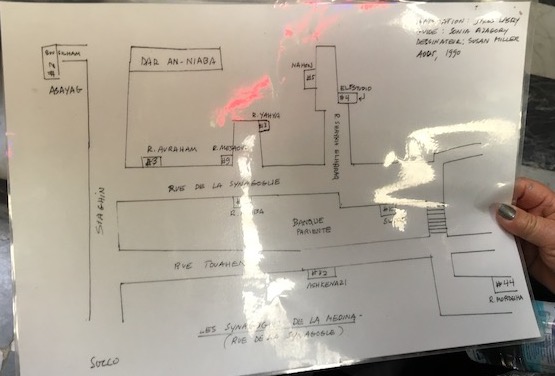

Just as with the Casablanca synagogue, services are held only on the high holidays, but a minyan (10 people) is usually gathered together for other ritual necessities. Similarly, too, the Tangier synagogue was immaculate but, other than the custodian, empty of people. Only this lone synagogue remains now, yet once there were 17 synagogues in Tangier, The custodian showed us a hand-made map charting the locations where they once stood.

The adjoining graveyard was sadly in ruined condition, but the names carved into the headstones, as well as the actual locations of the graves, had been gathered and thoughtfully digitized. We spent some time with the custodian poring over the print-out. Would we recognize any of these names as possible ancestors of Moroccan Jews we had met in Montreal?

“Do you have a donation for the synagogue?” the custodian asked.

* * * *

After this moving experience, and with my wallet a little lighter, we took a much-needed break for lunch. The décor in the cozy restaurant was, well, elaborately Moroccan, and the food fantastic. We especially enjoyed the bastillas, which each chef seems to make deliciously different. All the bastillas seem to contain chicken, are artistically baked in a crust. This may sound like Kentucky Fried Chicken, but it’s not in the same universe.

We had reserved the afternoon for souvenir shopping in the Bazaar, with its winding streets and alleyways. This is an area where you absolutely need a guide – unless you enjoy having four or five would-be sellers constantly dangling merchandise in front of your face. If you have a guide, they back off. Then you feel bad because you know they need to make a living.

Along with the abundant trivia, there were many quality shops in the Bazaar. Our guide knew all of the owners standing at the shop doors – there was much calling out of familiar names and expansive back-slapping – and he led us to a shop specializing in beautifully made antique silver, quite obviously rare and expensive. I fell in love with a single candlestick that had been crafted to look as if its base and stem were swirling flames, each flame inset with coral. The initial price started at $5,000, and slowly went down to $2,000 by the time I was going out the door. I am not a haggler; there was only one candlestick, and I wanted a pair. In any case, it was beyond my budget. Way beyond!

As I edged out the door, I noticed that lying on the chair holding it open were a few velvet tefillin (phylacteries) and tallit (prayer shawl) bags and – a little kippa (skullcap). It was tan suede with many little glass insets outlined in navy blue. Some of them were missing, but there was a red pom-pom on top. True, it was matted together, but I could wash it and brush it.

“Where is this from?” I asked.

“Oh, it’s used,” the sales attendant said scornfully. “It’s from the synagogue…when they renovated. They want to sell these things. But they’re used. We sell antiques.”

“All antiques are used,” I replied. “Only they’ve been used longer than this kippa.” The attendant didn’t know that I have been collecting kippas (new ones!) from synagogues in the many countries I have visited.

“It’s damaged, you know,” he told me. Some of the glass insets are missing.”

“But this kippa is authentic,” I said softly. “It’s small. Maybe a bar mitzvah boy wore it, right here in Morocco. Long ago. So…How much?”

“What you want to give,” he said, smiling broadly. “You know, it’s a donation for the synagogue.”

So I took another 20 Euros out of my wallet. And I was happy.

When I got home, I let the kippa soak overnight in a mixture of baking soda and warm water. In the morning I brushed the suede until it looked like new, and I untangled and trimmed the red pom-pom until it looked perky and festive.

And one day – maybe at Rosh Hashana (the Jewish New Year) — I will celebrate by wearing a Moroccan bar mitzvah boy’s kippa, crafted with artistry, and restored with love, to a synagogue service in sunny California. In my kavannah (mindful intention) before prayer, I will be giving continuity to the spiritual life of a Moroccan boy hopefully too young to be among the digitally recorded dead.

©Corinne Copnick, Los Angeles, 2019. All rights reserved.

By Rabbi Corinne Copnick

A paperback copy of a French-language book etched in my memory was entitled “Le Gout des Confitures” (“The Taste of Jam”). It was authored by Bob Ore, a Moroccan-born, Jewish businessman I knew long ago in his art-dealing capacity in Montreal. Forced by the Arab hostility toward Jews aroused in 1948 when Israel was declared a state — an anger that became dangerous when Morocco ceased to be a French protectorate in 1956 — he sought a new version of his life in other countries. After first attempting to settle in both France and Israel, Ore immigrated to French-speaking Montreal. Like many immigrants, his book explains, he never felt completely at home anywhere other than the land of his birth. In France, he was not French enough; in Israel, he was not a sabra; in Quebec, he was not Quebecois, but at least, au moins, he was not un anglais (although he spoke both English and French fluently).

His yearning for the sunny skies, the flowers, the multiple cultures and languages of Morocco, and especially the friendships scattered around the world, express the loss of what was once near and dear felt by first-generation immigrants everywhere.

In the years before Ore found his way to Canada, with lots of business acumen to sustain him, 250,000 Jews lived in Morocco. They had lived in that North African country for centuries, even thousands of years, many emigrating there long before the Romans conquered Israel and destroyed the Temple in the early common era. Native to Morocco when those first Jewish immigrants arrived were the Berbers, and the Jews got along with that indigenous population very well. In fact, a considerable number of Berbers even converted to Judaism. Morocco grew prosperous.

In the 15th and 16th centuries C.E., the Spanish Inquisition brought a different group of Jewish immigrants to the island, this time conversos fleeing for their lives. Seemingly converted to Christianity, most of them lived secret lives as Jews. Even so, the long arm of the Inquisition tried to reach into Morocco to punish the secret Jews they detected, but with little success. The Moroccan population did not cooperate. Why disturb the country’s prosperity, aided in large measure by the Jews? And the Jewish community continued to build and celebrate a substantial Jewish life.

Today, a large drawing by a contemporary artist is prominently displayed in the small, four-room Jewish museum in Casablanca. It depicts many of the Inquisition’s “penitents.” They are being forced to repent for the crime of remaining Jewish, and so they wear tall, pointed hats to mark their humiliation and reduced status. Some penitents are depicted with ropes around their necks. Since they have renounced Judaism, they will suffer an easier death: they will be strangled before being burnt at the stake.

The museum itself portrays a different message. Attractively built in recent years, the museum is sponsored by King Hassan II. Like his father, King Mohammed VI, before him, who tried to protect Moroccan Jews from the French Vichy regime during World War II, Hassan promotes harmony and toleration in his kingdom. At the entrance, a large plaque bearing the king’s signature and commemorating the opening of the museum, proclaims that all peoples and religions may live in harmony and peace together in Morocco. There is a picture of the head of the Jewish community shaking hands with a government official.

Billed as the only Jewish museum in the Arab world, it has multiple cases filled with magnificent antique Berber jewelry. Photographs of Jews living happily in Morocco decorate the walls throughout the four rooms. A large bima (platform) from a Casablanca synagogue that formerly existed stands in the middle of the largest room. I climbed the steps to the bima and looked over the dark-wood railing, a rabbi addressing the congregation that wasn’t there. The ark holds three large Torahs clothed in soft, velvet mantles, which rather surprised me. I had expected cylindrical Sephardic Torahs. Some of the most interesting contents of the museum can be viewed on multiple sites on the Internet. Many of the artifacts depicting Jewish life, however, are from the 1950s.

But where are the Jews now? The Moroccan climate is great; the food is fantastic; the people are welcoming; the newly restored but small synagogue is there. It provides a considerable contrast to Casablanca’s magnificent Hassan II Mosque (completed in 1993), the largest in Africa and fifth largest in the world, and elaborately built at such great cost (reputed to be $800 million),with hand-carvings decorating every inch and a retractable roof (there is no air-conditioning), its construction (completed in 1993) nearly bankrupted Morocco, and the citizenry had to be taxed to pay for it. It has a capacity of 25,000 inside and another 80,000 outside for large holidays like Ramadan. As I was guided through, I was awed by its immensity – the minaret stands at 60 stories high, it faces the Atlantic Ocean — and could only imagine what it must look like when devout Muslims fill it for prayer.

But the synagogue is empty. When necessary – a funeral, a yarzheit, another ritual event – the remaining Jews of Casablanca gather a minyan (the requisite 10 people to hold a service). The diminishing Jewish community celebrates the high holidays as best they can. And this year for Passover, there was a colorful poster showing that a Seder (a ritual feast celebrating the biblical liberation from slavery in Egypt) would take place at a stunning hotel in picturesque Marrakesh. The food would be kosher, and the 8-day stay would only cost $1590 Euros ($1900 US) per person (considered very reasonable).

Still, most of the Jews who come to Morocco are tourists, and Morocco is actively trying to promote its Jewish tourist trade. The children of Moroccan parents and grandparents come to visit the graves, but they don’t live there, in what is essentially an Arab culture. Dress is not legislated, although most Arab women I saw wore traditional dress, including the hijab (head scarf). Their tunics were colorful, and few black abayas (cloaks) or face veils were seen.

The bottom line? An estimated 2,500 Jews now live in Morocco, the majority in Casablanca. Most of them are elderly and some infirm. Unless the community is reinforced, it will soon disappear by attrition. What will remain is the memory – the taste, the gout, for what was left behind, the love for what has been, but is not now, and can never be again: the je ne sais quoi of a long-lost taste of jam.

©Corinne Copnick, Los Angeles, 2019. All rights reserved.

.