By Rabbi Corinne Copnick

Just as my daughter and I had visited the lovingly restored, small synagogue in Casablanca, it was important to us to visit the old synagogue in Tangier, located by winding our way through the maze of alleys adjacent to the Bazaar (the shouk or marketplace). By pre-arrangement, our guide pressed a buzzer, and a custodian opened the gate.

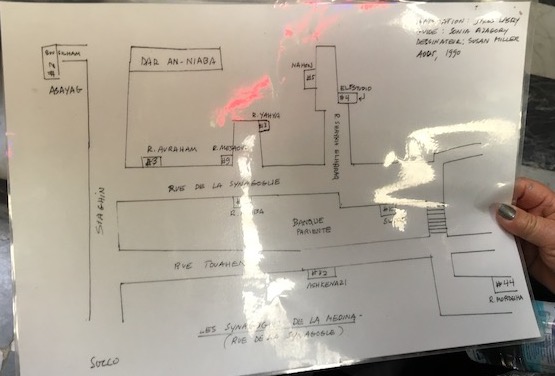

Just as with the Casablanca synagogue, services are held only on the high holidays, but a minyan (10 people) is usually gathered together for other ritual necessities. Similarly, too, the Tangier synagogue was immaculate but, other than the custodian, empty of people. Only this lone synagogue remains now, yet once there were 17 synagogues in Tangier, The custodian showed us a hand-made map charting the locations where they once stood.

The adjoining graveyard was sadly in ruined condition, but the names carved into the headstones, as well as the actual locations of the graves, had been gathered and thoughtfully digitized. We spent some time with the custodian poring over the print-out. Would we recognize any of these names as possible ancestors of Moroccan Jews we had met in Montreal?

“Do you have a donation for the synagogue?” the custodian asked.

* * * *

After this moving experience, and with my wallet a little lighter, we took a much-needed break for lunch. The décor in the cozy restaurant was, well, elaborately Moroccan, and the food fantastic. We especially enjoyed the bastillas, which each chef seems to make deliciously different. All the bastillas seem to contain chicken, are artistically baked in a crust. This may sound like Kentucky Fried Chicken, but it’s not in the same universe.

We had reserved the afternoon for souvenir shopping in the Bazaar, with its winding streets and alleyways. This is an area where you absolutely need a guide – unless you enjoy having four or five would-be sellers constantly dangling merchandise in front of your face. If you have a guide, they back off. Then you feel bad because you know they need to make a living.

Along with the abundant trivia, there were many quality shops in the Bazaar. Our guide knew all of the owners standing at the shop doors – there was much calling out of familiar names and expansive back-slapping – and he led us to a shop specializing in beautifully made antique silver, quite obviously rare and expensive. I fell in love with a single candlestick that had been crafted to look as if its base and stem were swirling flames, each flame inset with coral. The initial price started at $5,000, and slowly went down to $2,000 by the time I was going out the door. I am not a haggler; there was only one candlestick, and I wanted a pair. In any case, it was beyond my budget. Way beyond!

As I edged out the door, I noticed that lying on the chair holding it open were a few velvet tefillin (phylacteries) and tallit (prayer shawl) bags and – a little kippa (skullcap). It was tan suede with many little glass insets outlined in navy blue. Some of them were missing, but there was a red pom-pom on top. True, it was matted together, but I could wash it and brush it.

“Where is this from?” I asked.

“Oh, it’s used,” the sales attendant said scornfully. “It’s from the synagogue…when they renovated. They want to sell these things. But they’re used. We sell antiques.”

“All antiques are used,” I replied. “Only they’ve been used longer than this kippa.” The attendant didn’t know that I have been collecting kippas (new ones!) from synagogues in the many countries I have visited.

“It’s damaged, you know,” he told me. Some of the glass insets are missing.”

“But this kippa is authentic,” I said softly. “It’s small. Maybe a bar mitzvah boy wore it, right here in Morocco. Long ago. So…How much?”

“What you want to give,” he said, smiling broadly. “You know, it’s a donation for the synagogue.”

So I took another 20 Euros out of my wallet. And I was happy.

When I got home, I let the kippa soak overnight in a mixture of baking soda and warm water. In the morning I brushed the suede until it looked like new, and I untangled and trimmed the red pom-pom until it looked perky and festive.

And one day – maybe at Rosh Hashana (the Jewish New Year) — I will celebrate by wearing a Moroccan bar mitzvah boy’s kippa, crafted with artistry, and restored with love, to a synagogue service in sunny California. In my kavannah (mindful intention) before prayer, I will be giving continuity to the spiritual life of a Moroccan boy hopefully too young to be among the digitally recorded dead.

©Corinne Copnick, Los Angeles, 2019. All rights reserved.