Yizkor: Remembering [1]

by Rabbi Corinne Copnick

We have to accept that our flesh and blood, earthly lives – all life, our lives, the lives of our parents — eventually come to an end. But that understanding does little to reduce the pain of watching an ailing parent, a beloved parent, decline and deteriorate when there is nothing more we can do to reverse the effects of nature. In many instances — if we are lucky — this is our first personal encounter with death, and it brings into question our own mortality. It is painful to lose our beloved protector, not the protector of theology or the supernatural one of fiction, but our own personal protector who participated in giving us life.

Death is a homecoming, according to Abraham Joshua Heschel. In the final analysis, in the same way one prepares for life, one must prepare for death and depart with a sense of peace. “The Jewish mystical tradition sees old age in a positive light,” writes Rabbi A. J. Seltzer. “Aging is not seen as a defect to be eliminated by medical science. Old age presents the opportunity for the divine soul to assert primacy over the animal soul….The more the powers of the body subside and the fires of passion ebb, the stronger the spirit becomes…and the greater its joy over what it knows.” _

* * * *

As I helped feed my father in the dining room of the hospital for the aged where he was confined, I slowly became aware of an incessant refrain. It came from a nearby elderly female body, twisted and deformed. Professionally, a uniformed attendant continued spooning soup into the old lady’s mouth. The soup dribbled down her chin while she chanted over and over again in Yiddish, “Ich vil nor leben, ich vil nor leben!” (“I want to go on living. I still want to live.”)

The confused floor for the totally helpless. Despite all assurances, I was not prepared for my father’s placement in surroundings where his companions were those who had lost their way in the world. My father had been a member of a healing profession. Now the healer could not be healed. I was not ready for this reality.

Nor was I prepared for the fact that my mother would be spending part of every day at the home-hospital and feeling guilty if she missed a morning. She had already tended him, confused and incontinent, for nine years by herself at home. She had been coming to the hospital every day for four years. She had exhausted her self and her financial resources. And so we moved the man that we both loved from this friendly, sectarian hospital to a larger government hospital – bright and airy – twenty miles away. My father had been an officer in the army, and this was a hospital for veterans.

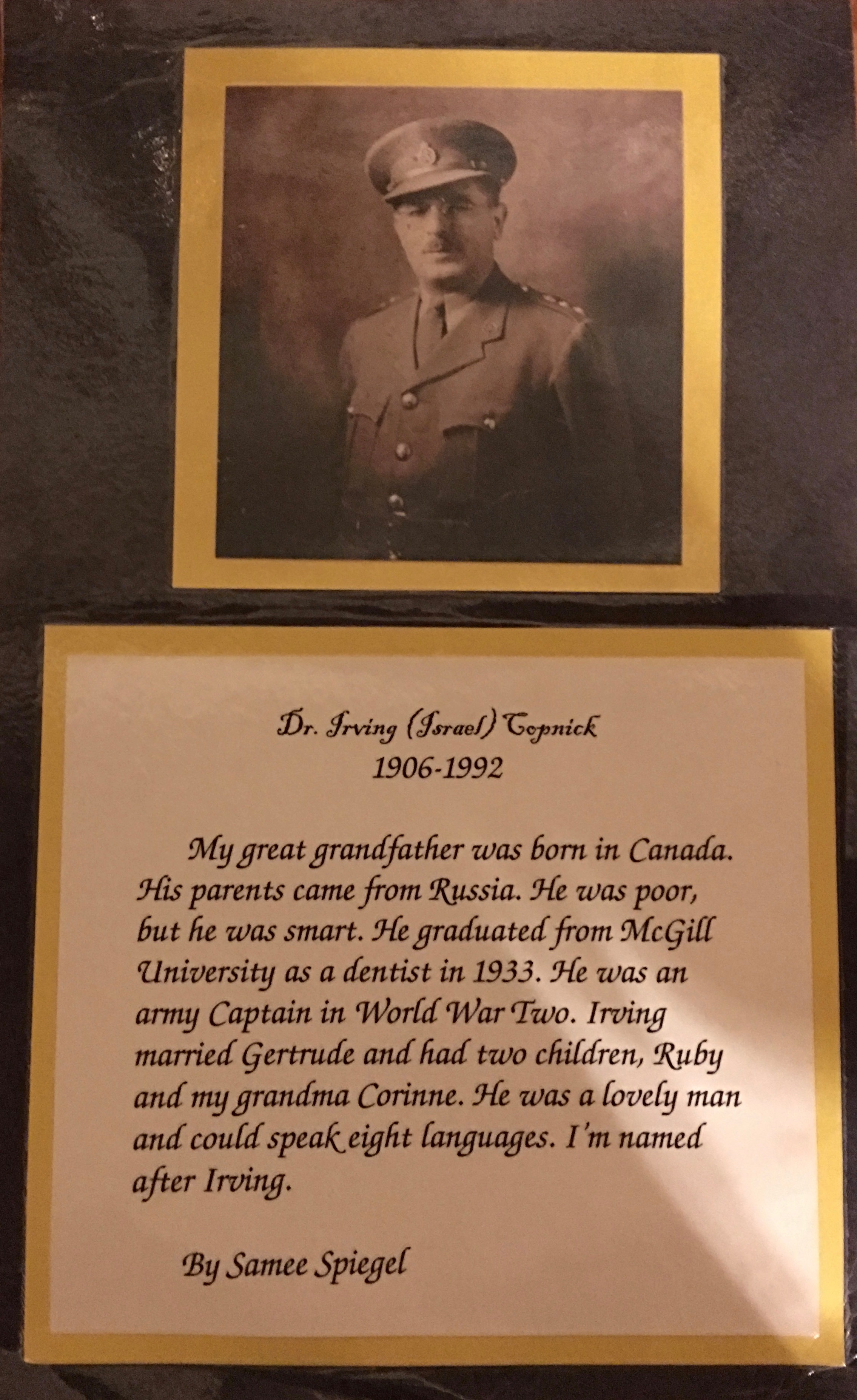

When I walked through these halls lined with men occasionally saluting one another, reliving their days as heroes, remembering when they were healthy and went to war for their country, I could remember myself as a little girl, standing proudly beside my father, so handsome in his new Captain’s uniform. Together we peered through the venetian blinds at the parade of soldiers smartly marching in unison several stories below.

My father….

I have come to accept that even when the loved one does not know you anymore, even when a gleam in the eye can no longer be evoked, there is still a breath of fresh air, a ray of sunshine, a taste of cool ice cream. These were the things my father could enjoy. Or the touch of my hand even if he didn’t know it was mine. And when, just once, he tapped his foot in sudden response to a familiar song, I knew my father was, for those few seconds, alive in spirit for me.

In this more distant setting, we do not visit as often now. We feel the need to detach ourselves from the accumulation of what is now more than twenty years’ witness to suffering, to remove ourselves from continually reliving the pain. But although he know longer knows us, he is still ours. Still a part of us. Neither can we abandon him.

“You understand, darling,” my father had written to me during the war when I was just a little girl, “your father is a doctor and a soldier. I dream of you every night, and I pray to God to protect you while I am gone. I miss you terribly, but soon, very soon, I shall come home again.”

I knew that I had brought my father to his last home. For that is the dread of placement – that it is final – a stepping stone to death. Only death will secure one’s release, once admitted, from these walls. And you can’t get out of death alive. That is what is so hard to face. That in placing someone you love, you must come to terms with your own mortality too.

What placing my father, with all its attendant sorrows, has given me that is positive, is a deeper understanding of the sanctity of life. That while the heart beats, there must be dignity, and that while the heart beats, there must be joy.

There is always compensation. When we placed my father here – his death in life – my mother began to live again. Who can know the mind of God?

* * * *

There is so much that we do not know about life and death in this world and the next. My father had not been able to utter a word for eleven years, nor to give any evidence that he heard the tender words with which my mother and I caressed him when we visited. Then, on a day that was earth-shaking for me, I told him that I was going to teach a course at McGill University (something I knew that he would prize), and for the next thirty seconds or so, my father burst into speech. He spoke to me in Yiddish (his first language as a young boy, but one with which he never addressed me), and the cascade of words told me how much he loved me, that I was the finest, the best. These words were the last my father, my earthly protector, ever spoke to me – or to anyone. They were his last words.

I will always remember.

©️Corinne Copnick, Toronto, 1992, Los Angeles 2015, 2017. All rights reserved.

* * * *

[1] “Yizkor” originally titled“ The Loss of the Protector,” is reprinted from an editorialized version in my 2015 thesis, “The Staying Power of Hope in the Aggadic Narratives of the Talmud.” It was first told in “Altar Pieces” (1992), a narrated collage of my original stories and poems that was videotaped and screened nationally many times on Canada’s “Vision TV” over a period of five years.