By Rabbi Corinne Copnick

“May I suggest that [human] potential for change and growth is much

greater than we are willing to admit, and that old age… be regarded as

the age of opportunities for inner growth.”

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel

Recently I read Richard Siegel and Rabbi Laura Geller’s newly published book, Getting Good at Getting Older, with great interest. It’s an excellent resource, beautifully designed with pages filled with helpful ideas and information about different organizations. In addition to the easy-to-read text. It’s also peppered with humor and inspirational quotes. Its target audience, as Rabbi Geller acknowledges, is the boomer group, people now in their 60s (perhaps newly retired or considering retirement), and into the mid-seventies (for those who “boomed” earlier).

What “Getting Good at Getting Older” does not cover, though, are those who got older some time ago, those in their late 70s, 80s, and 90s. Some of them apparently got really good at it because, if you follow your local obituaries, you’ll notice the growing number of people who have lived to pass the century mark.

In his gripping article, “A Secret Aging: How You Can Ward Off Death,” Rabbi Bradley Shavit Artson notes that that even in the Middle Ages, Rabbi Ibn Ezra wrote about Moses and Aaron’s old age in a complimentary fashion. For Ibn Ezra, their advanced age as these leaders accomplished great deeds was a source of pride for B’nei Israel.

The Talmud tells us, as Rabbi Artson also mentions, that human destiny is to live to the age of three score and 10 [70 years], but that those who have “strength” can live to 80. Thus 80 years is defined as the age of strength in the Talmud, and Artson defines this strength primarily as wisdom.

“The strength of 80 is the wisdom that comes from experience and completion. Having run much of the course of life, an adult of 80 years is finally able to look at the human condition with compassion and some skepticism. At 80, we no longer serve either passion or ambition.”

In my own experience, as I am approaching my mid-80s, what Rabbi Artson says is largely true, but there is more. Granted there is the wisdom, understanding, compassion — and sense of history, I would add — that comes from having experienced the ups and downs of living a long time. But I disagree when it comes to people in their 80s no longer having the need to serve passion. In my view, it’s the passion that keeps you going! Otherwise you’re in danger of folding up your personal tent.

For me, the strength of living into one’s 80s, and, hopefully, beyond, comes from the will to continue. It comes from believing you still have something to contribute, both concretely and by passing on your wisdom and experience (and money, if it hasn’t run out and you still have some). If the younger generations are truly willing to listen and don’t discard what you have to offer as irrelevant today, maybe your assistance will help them to achieve their goals in a world that has changed exponentially, not only with every generation but with every decade now. As for the boomers, they have already learned that paradoxical truth, “plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose (the more things change, the more they stay the same).”

My own four children, close together in age, are all tail-end (or almost tail-end) baby boomers. I believe with all my heart that they will continue to succeed, continue to grow as they get older, that they will be good at it. And when, God willing, they reach “the age of strength,” the age when Rabbi Artson says that younger people “can put off death by honoring the old among us,” I hope they, too, when the time comes, will have the will to continue — with passion — beyond honor, beyond past achievement. Perhaps they will also have learned that no matter how smart we humans are, no matter how much we are assisted by continually advancing artificial intelligence, none of us truly knows what the future holds. That’s God’s job.

By Rabbi Corinne Copnick

Just as my daughter and I had visited the lovingly restored, small synagogue in Casablanca, it was important to us to visit the old synagogue in Tangier, located by winding our way through the maze of alleys adjacent to the Bazaar (the shouk or marketplace). By pre-arrangement, our guide pressed a buzzer, and a custodian opened the gate.

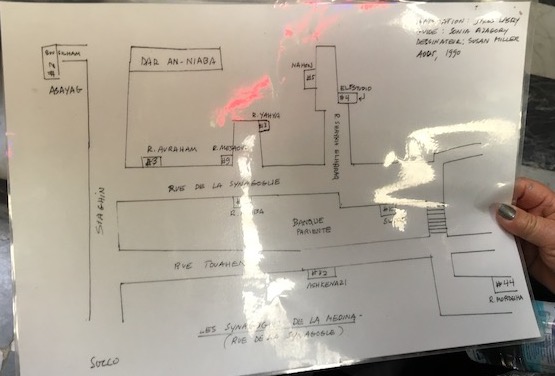

Just as with the Casablanca synagogue, services are held only on the high holidays, but a minyan (10 people) is usually gathered together for other ritual necessities. Similarly, too, the Tangier synagogue was immaculate but, other than the custodian, empty of people. Only this lone synagogue remains now, yet once there were 17 synagogues in Tangier, The custodian showed us a hand-made map charting the locations where they once stood.

The adjoining graveyard was sadly in ruined condition, but the names carved into the headstones, as well as the actual locations of the graves, had been gathered and thoughtfully digitized. We spent some time with the custodian poring over the print-out. Would we recognize any of these names as possible ancestors of Moroccan Jews we had met in Montreal?

“Do you have a donation for the synagogue?” the custodian asked.

* * * *

After this moving experience, and with my wallet a little lighter, we took a much-needed break for lunch. The décor in the cozy restaurant was, well, elaborately Moroccan, and the food fantastic. We especially enjoyed the bastillas, which each chef seems to make deliciously different. All the bastillas seem to contain chicken, are artistically baked in a crust. This may sound like Kentucky Fried Chicken, but it’s not in the same universe.

We had reserved the afternoon for souvenir shopping in the Bazaar, with its winding streets and alleyways. This is an area where you absolutely need a guide – unless you enjoy having four or five would-be sellers constantly dangling merchandise in front of your face. If you have a guide, they back off. Then you feel bad because you know they need to make a living.

Along with the abundant trivia, there were many quality shops in the Bazaar. Our guide knew all of the owners standing at the shop doors – there was much calling out of familiar names and expansive back-slapping – and he led us to a shop specializing in beautifully made antique silver, quite obviously rare and expensive. I fell in love with a single candlestick that had been crafted to look as if its base and stem were swirling flames, each flame inset with coral. The initial price started at $5,000, and slowly went down to $2,000 by the time I was going out the door. I am not a haggler; there was only one candlestick, and I wanted a pair. In any case, it was beyond my budget. Way beyond!

As I edged out the door, I noticed that lying on the chair holding it open were a few velvet tefillin (phylacteries) and tallit (prayer shawl) bags and – a little kippa (skullcap). It was tan suede with many little glass insets outlined in navy blue. Some of them were missing, but there was a red pom-pom on top. True, it was matted together, but I could wash it and brush it.

“Where is this from?” I asked.

“Oh, it’s used,” the sales attendant said scornfully. “It’s from the synagogue…when they renovated. They want to sell these things. But they’re used. We sell antiques.”

“All antiques are used,” I replied. “Only they’ve been used longer than this kippa.” The attendant didn’t know that I have been collecting kippas (new ones!) from synagogues in the many countries I have visited.

“It’s damaged, you know,” he told me. Some of the glass insets are missing.”

“But this kippa is authentic,” I said softly. “It’s small. Maybe a bar mitzvah boy wore it, right here in Morocco. Long ago. So…How much?”

“What you want to give,” he said, smiling broadly. “You know, it’s a donation for the synagogue.”

So I took another 20 Euros out of my wallet. And I was happy.

When I got home, I let the kippa soak overnight in a mixture of baking soda and warm water. In the morning I brushed the suede until it looked like new, and I untangled and trimmed the red pom-pom until it looked perky and festive.

And one day – maybe at Rosh Hashana (the Jewish New Year) — I will celebrate by wearing a Moroccan bar mitzvah boy’s kippa, crafted with artistry, and restored with love, to a synagogue service in sunny California. In my kavannah (mindful intention) before prayer, I will be giving continuity to the spiritual life of a Moroccan boy hopefully too young to be among the digitally recorded dead.

©Corinne Copnick, Los Angeles, 2019. All rights reserved.

By Rabbi Corinne Copnick

A paperback copy of a French-language book etched in my memory was entitled “Le Gout des Confitures” (“The Taste of Jam”). It was authored by Bob Ore, a Moroccan-born, Jewish businessman I knew long ago in his art-dealing capacity in Montreal. Forced by the Arab hostility toward Jews aroused in 1948 when Israel was declared a state — an anger that became dangerous when Morocco ceased to be a French protectorate in 1956 — he sought a new version of his life in other countries. After first attempting to settle in both France and Israel, Ore immigrated to French-speaking Montreal. Like many immigrants, his book explains, he never felt completely at home anywhere other than the land of his birth. In France, he was not French enough; in Israel, he was not a sabra; in Quebec, he was not Quebecois, but at least, au moins, he was not un anglais (although he spoke both English and French fluently).

His yearning for the sunny skies, the flowers, the multiple cultures and languages of Morocco, and especially the friendships scattered around the world, express the loss of what was once near and dear felt by first-generation immigrants everywhere.

In the years before Ore found his way to Canada, with lots of business acumen to sustain him, 250,000 Jews lived in Morocco. They had lived in that North African country for centuries, even thousands of years, many emigrating there long before the Romans conquered Israel and destroyed the Temple in the early common era. Native to Morocco when those first Jewish immigrants arrived were the Berbers, and the Jews got along with that indigenous population very well. In fact, a considerable number of Berbers even converted to Judaism. Morocco grew prosperous.

In the 15th and 16th centuries C.E., the Spanish Inquisition brought a different group of Jewish immigrants to the island, this time conversos fleeing for their lives. Seemingly converted to Christianity, most of them lived secret lives as Jews. Even so, the long arm of the Inquisition tried to reach into Morocco to punish the secret Jews they detected, but with little success. The Moroccan population did not cooperate. Why disturb the country’s prosperity, aided in large measure by the Jews? And the Jewish community continued to build and celebrate a substantial Jewish life.

Today, a large drawing by a contemporary artist is prominently displayed in the small, four-room Jewish museum in Casablanca. It depicts many of the Inquisition’s “penitents.” They are being forced to repent for the crime of remaining Jewish, and so they wear tall, pointed hats to mark their humiliation and reduced status. Some penitents are depicted with ropes around their necks. Since they have renounced Judaism, they will suffer an easier death: they will be strangled before being burnt at the stake.

The museum itself portrays a different message. Attractively built in recent years, the museum is sponsored by King Hassan II. Like his father, King Mohammed VI, before him, who tried to protect Moroccan Jews from the French Vichy regime during World War II, Hassan promotes harmony and toleration in his kingdom. At the entrance, a large plaque bearing the king’s signature and commemorating the opening of the museum, proclaims that all peoples and religions may live in harmony and peace together in Morocco. There is a picture of the head of the Jewish community shaking hands with a government official.

Billed as the only Jewish museum in the Arab world, it has multiple cases filled with magnificent antique Berber jewelry. Photographs of Jews living happily in Morocco decorate the walls throughout the four rooms. A large bima (platform) from a Casablanca synagogue that formerly existed stands in the middle of the largest room. I climbed the steps to the bima and looked over the dark-wood railing, a rabbi addressing the congregation that wasn’t there. The ark holds three large Torahs clothed in soft, velvet mantles, which rather surprised me. I had expected cylindrical Sephardic Torahs. Some of the most interesting contents of the museum can be viewed on multiple sites on the Internet. Many of the artifacts depicting Jewish life, however, are from the 1950s.

But where are the Jews now? The Moroccan climate is great; the food is fantastic; the people are welcoming; the newly restored but small synagogue is there. It provides a considerable contrast to Casablanca’s magnificent Hassan II Mosque (completed in 1993), the largest in Africa and fifth largest in the world, and elaborately built at such great cost (reputed to be $800 million),with hand-carvings decorating every inch and a retractable roof (there is no air-conditioning), its construction (completed in 1993) nearly bankrupted Morocco, and the citizenry had to be taxed to pay for it. It has a capacity of 25,000 inside and another 80,000 outside for large holidays like Ramadan. As I was guided through, I was awed by its immensity – the minaret stands at 60 stories high, it faces the Atlantic Ocean — and could only imagine what it must look like when devout Muslims fill it for prayer.

But the synagogue is empty. When necessary – a funeral, a yarzheit, another ritual event – the remaining Jews of Casablanca gather a minyan (the requisite 10 people to hold a service). The diminishing Jewish community celebrates the high holidays as best they can. And this year for Passover, there was a colorful poster showing that a Seder (a ritual feast celebrating the biblical liberation from slavery in Egypt) would take place at a stunning hotel in picturesque Marrakesh. The food would be kosher, and the 8-day stay would only cost $1590 Euros ($1900 US) per person (considered very reasonable).

Still, most of the Jews who come to Morocco are tourists, and Morocco is actively trying to promote its Jewish tourist trade. The children of Moroccan parents and grandparents come to visit the graves, but they don’t live there, in what is essentially an Arab culture. Dress is not legislated, although most Arab women I saw wore traditional dress, including the hijab (head scarf). Their tunics were colorful, and few black abayas (cloaks) or face veils were seen.

The bottom line? An estimated 2,500 Jews now live in Morocco, the majority in Casablanca. Most of them are elderly and some infirm. Unless the community is reinforced, it will soon disappear by attrition. What will remain is the memory – the taste, the gout, for what was left behind, the love for what has been, but is not now, and can never be again: the je ne sais quoi of a long-lost taste of jam.

©Corinne Copnick, Los Angeles, 2019. All rights reserved.

.

By Rabbi Corinne Copnick

Last week I wrote about the immense, cathedral-like environment carved out of a lava tube on Canary Islands’ Lanzarote by inspired nature-artist Cesar Manrique. Among many other projects, he also created a huge, park-like, otherworldly environment, Jardin de Cactus, featuring more than 1,100 species of cacti planted in what was a disused quarry – that is, until Manrique, who is also an architect, decided to accent nature with art and vice-versa there. He and his talented team created an jaw-dropping garden of carefully landscaped and tended cacti, accented with red rocks, bridges, paved paths and even pools at different levels.

These are not little or even medium-sized cacti, oh no! Everything is grand in scale, plants that have been nurtured in the volcanic soil for many years. They range, according to the Jardin’s information, “from towering saguaros and spiny over-sized globes to more unusual species that resemble giant white maggots, thrusting asparagus spears, prickly mounds of broccoli, or dark green corals and sea anemones.” All have been planted in close proximity to one another in artistic patterns. The result, which took 20 years to complete, is astoundingly beautiful.

It was springtime when we visited, my daughter and I. And so many of the cacti were in bloom. It took my breath away. The word “awesome” seemed almost inadequate.

For me, visiting the Jardin de Cactus was a Heschel moment. Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel has long captured my imagination with his concept of “radical amazement,” which thankfully continues to influence every day of my life. As Heschel wrote about in his stellar books, “God in Search of Man: A Philosophy of Judaism,” and “Moral Grandeur and Spiritual Audacity,” that we should live our lives with a sense of wonder: to be spiritual is to be amazed. We should get up every morning with an appreciation of being alive, he explained, with a sense of awe at the mystery of life, and the desire to celebrate it.

That sense of wonder certainly resonated in me at the Jardin. It was springtime when my daughter and I visited. And so many of the cacti were in bloom in response to the balmy weather. It took my breath away. Although I understood that cacti have many practical uses in the desert, I didn’t know that cacti are actually flowering plants. The word “awesome” seemed almost inadequate.

I did know about the “monocarpic” century plant, so biologically labelled because it is a cactus said to bloom only once in 100 years (although some century plants have been known to bloom much sooner, perhaps in a few decades, depending on the climate, soil, and care they get). Unfortunately, after the century plant (horticulturally categorized as an “Agave americana”) blooms, it usually dies. I took a long look at one of the Jardin’s century plants; it reminded me of male worker bees who, once they mate with the Queen Bee, also die after this moment of glory.

It also reminded me that I still have a way to go before my final bloom. My human generation seems to have an unusual number of centenarians, so it’s comforting to know that at least a few century plants, like most cacti, are repeat bloomers.

Fortunately, most humans have the capacity to be repeat bloomers, as indeed Cesar Manrique’s many projects testify. The Jardin de Cactus was his last project – his final artistic bloom — completed in the 1990s. Two years later, he died in a car crash. His beautiful creations, however, live on in the volcanic soil. Truly awesome!

Awesome too, was the excitement of one of our fellow tourists, a retired surgeon from California, who was almost dancing with joy as he checked out the cacti in the garden. “I have two greenhouses at home, with 400 varieties of cacti growing,” he exulted. “And I can identify so many of the cacti in the Jardin. Of course, my cacti are little. I love to take care of them.”

“Do they bloom yet?” I asked this brilliant man, who had become our friend, who, after so many years of doctoring, still loved to care for living things.

“Not yet,” he replied. “But now I know they will.”

Our tour guide almost had to pull him out of the garden to rejoin the bus. He simply didn’t want to leave the cacti blooming, as if just for us, on a lovely spring day.

Click link for video: Jardin de Cactus

By Rabbi Corinne Copnick

I had been inside a lava tube once before, a long time ago. The tube was in the Hawaiian Islands and amazingly cut right through a volcano that was still fitfully alive — the Kilauea volcano on Big Island, near the Hawaii Volcanic National Park. Apprehensive visitors like me might be experiencing some internal quaking of their own before entering the tube, but the attraction was irresistible: a 1,000-year-old, tropical rain forest. Right inside the rocky darkness of the lava tube! Such a beautiful, bountiful, colorful rain forest that its location strained credulity.

This volcano, one of five in Hawaii and estimated to be between 300,000 and 600,000 years old, was known to be temperamental. From time to time, it erupted, hurling its lava streams down the mountain into the sea. I remembered walking on another area of that same Hawaiian volcano, deemed “safe” for that afternoon by knowledgeable scientists (seismologists I think they are called) who took continual, up-to-the-minute readings of the volcano – and would change the visiting parameters accordingly. Still, my family and I (my husband and I were there with our four teenage children) could actually see red embers glowing here and there beneath the thin cracks in the black lava. Prominent signs warned visitors not to stay for more than a few minutes because of the sulphur fumes.

In more recent years, the Kilauea volcano erupted so forcefully that it destroyed everything in its wake. In fact, the eruption did in so much damage that the Hawaii Volcanic National Park had to be closed for some time.

* * * *

Decades have passed, and I am standing at the entrance to another natural wonder on a different island. This time it is a black lava tube on Lanzarote, in the Canarias (Canary Islands in English). These islands, infamous for dealings with pirates in past centuries, are part of Spain, but they are autonomous. It has taken six days at sea on the Atlantic Ocean to travel here from Barbados, our first stop. I am with my daughter, Janet (who, as it happens, was also with me when we visited the Kilauea lava tube). But this time an immensely talented man has joined forces with nature to create an aesthetic, unexpectedly spiritual, environment carved from the black rocks inside.

His name is Cesar Manirique, and, although I had never before heard of him, he is an internationally known and respected artist. His life’s work – he has since passed away — is built on the premise that art and nature in combination cannot be surpassed. His projects are large scale, and their effect is deeply moving. His major work is intentionally on Lanzarote, and they have brought fame – and tourists, with an accompanying boost to the economy — to an island created from ground-up, rocky soil as well. The landscape is dotted with small settlements of white, adobe-style houses clustered together on the black land, with a little greenery flourishing here and there.

My daughter, who rock climbs as a sport, jokes that I have also become a rock climber in Manirique’s lava tube. She calls it “scrambling.” I would call it something else – OMG — stooping as low to the ground as possible and clutching on to the jagged rocks like a railing as I climb the many steps carved further and further into the black tube. Soon my fears of falling disappear as I am overwhelmed by the aesthetic experience created by a master artist.

Manirique and his team have enlarged a natural opening in the rock in the shape of a perfect oval, so that those who enter the lava tube discover a magnificent view of the ocean and the looming mountains beyond. This exquisite sight from outside is reflected in a large, sky blue pool amid the rocks, bestowing a unity with the outside world on the lava tube’s environment. The water continually flows from the lava tube to the sea, so that the level of the water rises and falls with the tide. As I look at the pool with the eyes of a rabbi who serves as a dayan (a judge in a rabbinic court, a bet din), I realize that, unintentionally, Manrique has created a natural mikveh (body of water for ritual purification).

And when I look at the water and surrounding rocks more closely, I see that there are living things in this pool — tiny, albino spider-crabs, as small as spiders, but they are actually crabs – that keep the water clean.

We look at the pool for a long time. To further enhance its effect, Manirique has outlined the pool’s curving shape with a thick, white plaster substance, an artistic exclamation point, something he has repeated at various points throughout the lava tube experience.

There is even a small, charming restaurant close by, tables and chairs, more openings to the outside.

We climb more stairs, further into the tube. And then we enter a huge space carved out of the rocks, or maybe it is a natural space, a bubble in the lava tube. I gasp. My daughter gasps. The immense ceiling is so high. It is dimly lit. Benches carved from the black rock and accented with white plaster backs descend down a long, sloped aisle to what seems to be — a stage? — at its base. There are benches on the other side of the aisle too. Seating, we learn, for 1200 people. Classical concerts are given here at regular intervals. The acoustics are terrific, and the space has been wired for sound and additional lighting. Amazing.

It is an awesome space; it feels like a cathedral. I imagine that it is a synagogue at Rosh Hashana. On the stage, the bima, my mind projects an altar and there, just behind it, an Ark holding the Torah scrolls. The rabbi – is it me? a few of my colleagues taking turns with me, sharing the service ?– and a cantor are there. A choir? Of course. Are there people sitting on the benches? Throughout my visit to the Canary Islands, I have looked for Jewish history, for any evidence that there is still a synagogue in these islands (there is a small one in Las Palmas, and the Torah scroll that was once in Tenerife was sent there; however, the synagogue’s door is unmarked, and, in the brief time I was in Las Palmas, I could not find it).

Once, even before the Spanish and Portuguese Inquisitions, there was a humble Jewish community on this island, Lanzarote. Later there was a prosperous community of Portuguese Jews who fled their own land and built this island’s economy. Once…

I take a deep breath. At this moment in time, just for this beautiful moment, I have found what could serve as a synagogue deep in the rocks. Complete with mikveh – and catering service. And my daughter is by my side. Outside the sun is shining.

©Corinne Copnick, Los Angeles, 2019. All rights reserved.