By Rabbi Corinne Copnick

Over the past view months, Zoom online programming has been my window to the outside world. As it has with many of you, this new technology has made the viewpoints of my colleagues and friends available to me in these difficult pandemic times. I have learned so much from the thinking process and knowledge of others and offered my own as well. It has enabled me to see friendly faces I know, as well as those new to me, in mosaic tiles. And on Zoom, we can actually “see” one another, full face, for a while. We don’t need masks when we’re on the screen.

As a senior citizen in my eighties, I have the good fortune to live with two of my grown children and now a grandchild home from college as well. I do not have to watch television or have a Sabbath dinner alone. We have a beautiful garden in which to relax and have family meals outside. However, as a diabetic for the last 25 years, I do have a compromised immune system. So I have listened faithfully to the advice of our California government and our dedicated health experts and remained indoors since the beginning of March. It’s going on five months now. Apart from a daily walk around the block or so, and one quick visit to the beach on a day that it was “open,” I have not been “outside” since the “stay safe at home” instruction was issued.

At first I watched a lot of television, especially the daily comments of New York governor Andrew Cuomo, whose service to our nation has been invaluable. As a family, we caught up on recent TV series with “binge-watching.” We cooked and baked a lot. Courtesy of the Los Angeles library, I have read some thirty or so books online. Good books. I visited my doctor for an online appointment.

Perhaps most important, I have included in my daily schedule attending at least one Zoom lecture or teaching on a particular topic every single day. When it became too overwhelming—and tiring as well, because learning on Zoom requires a constant, single-focus attention, I restricted my Zoom screen time to one lecture a day. Gradually, I developed the confidence to successfully host and teach ten of my own sessions for my Beit Kulam adult education classes.

And I am proud to have mastered, at least to some small extent, and an online class helped, a new technology that can be a very “cold” medium for teaching—unless you learn how to make it “warm.” Recorded lectures tend to be on the cold side, and I have found that it’s best to have shorter bursts of “teaching,” with a lot of discussion, or guided discussion, in between.

Also, I find it takes away from concentration on what the main speaker is saying to have written material, or even visual material, on the screen while the speaker is talking. Better, in my experience, to use it, as an aid to discussion, before or after the topic at hand. At the moment, I’m not an enthusiast of the breakaway groups feature; so far, I have found this “small group” discussion experience rather limited in the time allowed. Still much to be learned about using it, so this reaction may change.

When I virtually presented my new book, “A Rabbi at Sea” in New York for the Jewish Book Council network, I saw how meticulous preparation and engagement could make a large scale event very successful. Where there’s a will—and a need that could otherwise be overwhelming—there’s a way!

* * * *

In the meantime, I have made myself available to my Beit Kulam members, should they have the need to talk about personal issues, on Friday mornings, and on Friday afternoons I virtually teach a private Torah class to my own daughter (I have four of them) and her non-Jewish partner in Vancouver. It has proved to be both a beautiful and calming experience before greeting Shabbat. Their “homework” is to read various commentaries about each week’s parsha before we read it aloud together. This past week we gave the gift of increasing strength to one another by reciting the traditional “Hazak, hazak, v’nitkazek” as the Book of Numbers ended and began Deuteronomy, the last book in the Torah, which largely summarizes what has happened in the previous four books.

So, for some people, the new technologies drive them nuts. For me, it has been a wonderful way to preserve my sanity amidst the labyrinth of dark and conflicting news broadcasts that now permeate our wonderful world. For me, the new technologies, bringing with them exposure to many points of views, are a saving grace. Can I help it if I’m naturally hopeful and optimistic?

I remember the devastating polio epidemic of my youth that so badly affected my mother’s cousin, Libbele, that she was paralyzed from the waist down for the rest of her life, confined to a wheelchair. But she had an indomitable spirit. She mastered many crafts, through which she made a small living, and her loving relatives made sure she was well supported, emotionally and financially, throughout her life.

Like the many other pandemics that permeate our world history (one of the four disasters that the Jewish holiday, Tisha B’Av, memorializes is the plague that killed 24,000 students of Rabbi Akivah), polio was eventually overcome (even though late age, second stage polio has unexpectedly entered our world) when Dr. Salk developed a vaccine. As I write this, our scientists around the world are working furiously to find the right vaccine to overcome Covid-19. With God’s help, they will. As Dr. Salk is famously quoted, “Hope lies in dreams, in imagination and in the courage of those who dare to make dreams into reality (www.salk.edu).”

By Rabbi Corinne Copnick

It was joyful, fantastic, overwhelming, and reinforced my belief that the catastrophic disaster called Covid-19 will eventually lead to world-shaping innovations that will improve our present society’s quality of life immeasurably. Call it a justification anew of that old adage: “Necessity is the Mother of Invention.” Call it the manifestation of a new, “woke” generation taking charge, sometimes overcharge. Call it a combination of education, science, ethics, the arts, and government—and a new regard for authentic historical experience of the past century and earlier (and the expertise of an older generation to which I belong that remembers it accurately because we’ve lived through it and its after-effects)—all working hand-in-hand to make life for human beings globally the best it can be in this new decade, the 2020s. Call it people have amazing inner resources when they are put to the test.

What great event stimulated my current overflow of optimism? It was the three-day conference of The Jewish Book Council (JBC), based in New York, but open to participants from all over the US and even beyond this year. Pre-Covid 19, for years this conference has been held in-person, providing an opportunity for writers accepted as touring writers of the JBC “network,” which, along with its many acclaimed authors, consists of member Jewish organizations from all over the country. It’s an exceptional opportunity not only to promote their new books, to present them in carefully-timed “pitches” and gain bookings before new audiences, but also to meet and greet, and feel that they are part of a literary whole that gives them new energy and inspiration to keep on writing.

Writing can be a very lonely business. So opportunities for writers to get together, especially in this year of Covid-19, where authors have been limited in large measure to telephone and computer screens, have loomed larger than ever. That is why the JBC in its wisdom, but taking on a huge task, decided to hold the conference virtually this year. Not only would the various member sessions be held virtually, but its writers also would present virtually. The outpouring of people who wanted to be included was phenomenal.

Making the virtual conference successful required meticulous and lengthy preparation, both for the technical aspects of such a large enterprise, for the member organizations, and for the writers. As a JBC network touring author, I had the benefit of Council staff working with me on two occasions to refine my presentation to the best it could be within the two minute requirement.

Why two minutes? Because over three days, eight groups of approximately 25 authors, each with substantial resumes and literary accomplishments, presented virtually to a member audience, also virtual, of a few hundred people taking notes. That’s a lot of authors to remember, even with a presenting cap of 2 minutes each (with a ding when your two minutes is up, just like the Academy Awards). For this reason, the JBC also put out a its own virtual (Pdf) book containing the details of each Council touring author’s offering and bio. In order to book an author for an event, the member organizations have to contact the Jewish Book Council.

We authors also were treated to a detailed technical rehearsal involving sound, lighting, when to keep our own video cameras and sound system on and off, an orderly procedure for each presentation, and so on. The technical people and administration throughout were not only supportive but very kind to people of different ages who had varied levels of experience with Zoom techniques. Everyone concerned put in their best effort. That’s why the conference—whose administration only a few months earlier could have conveniently canceled the event, was so successful that it is considering the possibility of going global next year. Wow!

And I think every single one of us who participated in making the conference successful, both for the organization and personally, feels very, very proud. Who’s going to let a virus, one that will probably be around for a long time, get us down? Of course, “broadcasting” from my own dining room table, with the technical assistance of my daughter, I didn’t have to wear a mask. But you can bet your bottom dollar I do and will wear one whenever it’s essential for me to leave the house (where I have mainly been sitting right beside my similarly housebound computer since the beginning of March). I want to be in good health to participate in next year’s conference.

Thank you once again to those who made it possible for me, mainly Miri, Suzanne, Naomi, and Jake—the personnel with whom I interacted, as well as all the writers who were in my presenting “cohort.”

Now we need some virtual bookings.

By Rabbi Corinne Copnick

“May I suggest that [human] potential for change and growth is much

greater than we are willing to admit, and that old age… be regarded as

the age of opportunities for inner growth.”

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel

Recently I read Richard Siegel and Rabbi Laura Geller’s newly published book, Getting Good at Getting Older, with great interest. It’s an excellent resource, beautifully designed with pages filled with helpful ideas and information about different organizations. In addition to the easy-to-read text. It’s also peppered with humor and inspirational quotes. Its target audience, as Rabbi Geller acknowledges, is the boomer group, people now in their 60s (perhaps newly retired or considering retirement), and into the mid-seventies (for those who “boomed” earlier).

What “Getting Good at Getting Older” does not cover, though, are those who got older some time ago, those in their late 70s, 80s, and 90s. Some of them apparently got really good at it because, if you follow your local obituaries, you’ll notice the growing number of people who have lived to pass the century mark.

In his gripping article, “A Secret Aging: How You Can Ward Off Death,” Rabbi Bradley Shavit Artson notes that that even in the Middle Ages, Rabbi Ibn Ezra wrote about Moses and Aaron’s old age in a complimentary fashion. For Ibn Ezra, their advanced age as these leaders accomplished great deeds was a source of pride for B’nei Israel.

The Talmud tells us, as Rabbi Artson also mentions, that human destiny is to live to the age of three score and 10 [70 years], but that those who have “strength” can live to 80. Thus 80 years is defined as the age of strength in the Talmud, and Artson defines this strength primarily as wisdom.

“The strength of 80 is the wisdom that comes from experience and completion. Having run much of the course of life, an adult of 80 years is finally able to look at the human condition with compassion and some skepticism. At 80, we no longer serve either passion or ambition.”

In my own experience, as I am approaching my mid-80s, what Rabbi Artson says is largely true, but there is more. Granted there is the wisdom, understanding, compassion — and sense of history, I would add — that comes from having experienced the ups and downs of living a long time. But I disagree when it comes to people in their 80s no longer having the need to serve passion. In my view, it’s the passion that keeps you going! Otherwise you’re in danger of folding up your personal tent.

For me, the strength of living into one’s 80s, and, hopefully, beyond, comes from the will to continue. It comes from believing you still have something to contribute, both concretely and by passing on your wisdom and experience (and money, if it hasn’t run out and you still have some). If the younger generations are truly willing to listen and don’t discard what you have to offer as irrelevant today, maybe your assistance will help them to achieve their goals in a world that has changed exponentially, not only with every generation but with every decade now. As for the boomers, they have already learned that paradoxical truth, “plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose (the more things change, the more they stay the same).”

My own four children, close together in age, are all tail-end (or almost tail-end) baby boomers. I believe with all my heart that they will continue to succeed, continue to grow as they get older, that they will be good at it. And when, God willing, they reach “the age of strength,” the age when Rabbi Artson says that younger people “can put off death by honoring the old among us,” I hope they, too, when the time comes, will have the will to continue — with passion — beyond honor, beyond past achievement. Perhaps they will also have learned that no matter how smart we humans are, no matter how much we are assisted by continually advancing artificial intelligence, none of us truly knows what the future holds. That’s God’s job.

By Rabbi Corinne Copnick

Even though Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall didn’t star in a movie about Tangier (who has not seen their fictional romance in Casablanca unfold on a cinema screen?), this busy port-city in Northwestern Morocco has a history to rival Casablanca. Its location at the western entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar – right where the Mediterranean Sea meets the Atlantic Ocean — has given Tangier a trade advantage over the years to the extent that in 1928 it was deemed an international city. Its history as an important port goes back to the time of the Phoenicians in the 10th century B.C.E. History, history, history!

And even though Tangier today is a lively, modern city with attractive landscaping, affluent neighborhoods, and important projects, my daughter and I wanted to visit the old Medina with its colorful mélange of shops and signs. Although it was, in part, once a thriving Jewish neighborhood in Tangier, none of the shops retained names that were likely to be Jewish anymore.

Unlike other cities in Morocco, Tangier never had a mellah (a walled and gated area where Jews were required to live, ostensibly for their own protection) similar to the European ghettos. Nevertheless, the Jewish inhabitants of Morocco understood that they were living in an Arab, mainly Islamic neighborhood, and that certain restrictions applied to non-Islamic residents who lived in Arab lands, including Morocco. Although Jews and Christians were both respected as “People of the Book,” they understood that they were considered inferior to Muslims and expected to defer to them in many ways. In addition, they had to pay a special tax for the privilege of living in Morocco. Basically, they were second-class citizens referred to as dhimmis.

Most of the time, the different religious groups understood their place in Moroccan society and got along very well, but, regrettably, over the centuries (the 8th century and again in the 15th century in the city of Fez, in particular), some large massacres of Jews took place. Centuries later, during the World War II Nazi regime in Germany and the pro-Nazi, Vichy government in France (Morocco , remember, was a French protectorate), many civil restrictions on Jews were put into place –despite the best efforts of the Moroccan King to prevent them.

When World War II ended in 1945, and after its own War of Independence, the State of Israel became a reality in 1948, Moroccan Jews found themselves targeted by a forceful Arab push for them to leave Morocco. Those who had the means immigrated to countries like Canada, France, and South America. At the same time, there was a strong biblical pull for the larger number of Moroccan Jews who for centuries had dreamed of making Aliyah (the ascent of return) to their spiritual home, Israel. And so the mid-20th century exodus to Israel began. In 2019, an estimated one million Jews of at least partial Moroccan ancestry are Israeli citizens – who still have tender feelings for Morocco.

©Corinne Copnick, Los Angeles, 2019. All rights reserved.

By Rabbi Corinne Copnick

Just as my daughter and I had visited the lovingly restored, small synagogue in Casablanca, it was important to us to visit the old synagogue in Tangier, located by winding our way through the maze of alleys adjacent to the Bazaar (the shouk or marketplace). By pre-arrangement, our guide pressed a buzzer, and a custodian opened the gate.

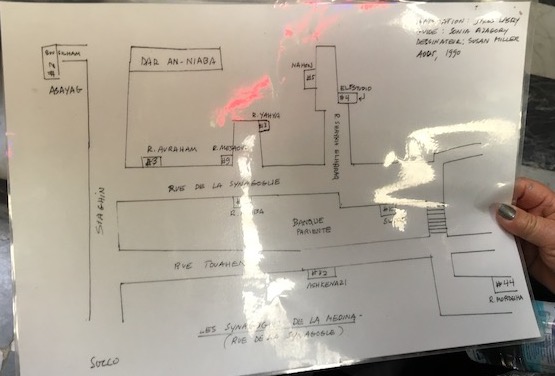

Just as with the Casablanca synagogue, services are held only on the high holidays, but a minyan (10 people) is usually gathered together for other ritual necessities. Similarly, too, the Tangier synagogue was immaculate but, other than the custodian, empty of people. Only this lone synagogue remains now, yet once there were 17 synagogues in Tangier, The custodian showed us a hand-made map charting the locations where they once stood.

The adjoining graveyard was sadly in ruined condition, but the names carved into the headstones, as well as the actual locations of the graves, had been gathered and thoughtfully digitized. We spent some time with the custodian poring over the print-out. Would we recognize any of these names as possible ancestors of Moroccan Jews we had met in Montreal?

“Do you have a donation for the synagogue?” the custodian asked.

* * * *

After this moving experience, and with my wallet a little lighter, we took a much-needed break for lunch. The décor in the cozy restaurant was, well, elaborately Moroccan, and the food fantastic. We especially enjoyed the bastillas, which each chef seems to make deliciously different. All the bastillas seem to contain chicken, are artistically baked in a crust. This may sound like Kentucky Fried Chicken, but it’s not in the same universe.

We had reserved the afternoon for souvenir shopping in the Bazaar, with its winding streets and alleyways. This is an area where you absolutely need a guide – unless you enjoy having four or five would-be sellers constantly dangling merchandise in front of your face. If you have a guide, they back off. Then you feel bad because you know they need to make a living.

Along with the abundant trivia, there were many quality shops in the Bazaar. Our guide knew all of the owners standing at the shop doors – there was much calling out of familiar names and expansive back-slapping – and he led us to a shop specializing in beautifully made antique silver, quite obviously rare and expensive. I fell in love with a single candlestick that had been crafted to look as if its base and stem were swirling flames, each flame inset with coral. The initial price started at $5,000, and slowly went down to $2,000 by the time I was going out the door. I am not a haggler; there was only one candlestick, and I wanted a pair. In any case, it was beyond my budget. Way beyond!

As I edged out the door, I noticed that lying on the chair holding it open were a few velvet tefillin (phylacteries) and tallit (prayer shawl) bags and – a little kippa (skullcap). It was tan suede with many little glass insets outlined in navy blue. Some of them were missing, but there was a red pom-pom on top. True, it was matted together, but I could wash it and brush it.

“Where is this from?” I asked.

“Oh, it’s used,” the sales attendant said scornfully. “It’s from the synagogue…when they renovated. They want to sell these things. But they’re used. We sell antiques.”

“All antiques are used,” I replied. “Only they’ve been used longer than this kippa.” The attendant didn’t know that I have been collecting kippas (new ones!) from synagogues in the many countries I have visited.

“It’s damaged, you know,” he told me. Some of the glass insets are missing.”

“But this kippa is authentic,” I said softly. “It’s small. Maybe a bar mitzvah boy wore it, right here in Morocco. Long ago. So…How much?”

“What you want to give,” he said, smiling broadly. “You know, it’s a donation for the synagogue.”

So I took another 20 Euros out of my wallet. And I was happy.

When I got home, I let the kippa soak overnight in a mixture of baking soda and warm water. In the morning I brushed the suede until it looked like new, and I untangled and trimmed the red pom-pom until it looked perky and festive.

And one day – maybe at Rosh Hashana (the Jewish New Year) — I will celebrate by wearing a Moroccan bar mitzvah boy’s kippa, crafted with artistry, and restored with love, to a synagogue service in sunny California. In my kavannah (mindful intention) before prayer, I will be giving continuity to the spiritual life of a Moroccan boy hopefully too young to be among the digitally recorded dead.

©Corinne Copnick, Los Angeles, 2019. All rights reserved.